2026-02-20

Accelerating Stream Processing in Production

We examine how RocksDB, Apache Fluss, and distributed caching layers address scaling challenges, providing both architectural guidance and practical configuration examples for production deployments.

Accelerating Stream Processing in Production

Stream processing has become foundational to modern data architectures, enabling organizations to derive real-time insights from continuous data flows. Apache Flink has emerged as the de facto standard for stateful stream processing, offering exactly-once guarantees, low-latency execution, and advanced state management.

However, scaling stream processing from proof-of-concept to production introduces significant challenges. State backends become bottlenecks, access to reference data introduces latency, and the gap between real-time streaming and batch analytics creates data freshness inconsistencies. Organizations that fail to address these blockers often struggle to meet latency requirements or see their pipelines fail to scale gracefully under increasing data volumes.

This article explores three architectural pressure points in production stream processing:

- Stateful scaling: Managing state that grows to terabytes

- Streaming-lakehouse integration: Bridging real-time and analytical systems

- Object storage latency: Accelerating access to reference data

We examine how RocksDB, Apache Fluss, and distributed caching layers address these challenges, providing both architectural guidance and practical configuration examples for production deployments.

Contents

- 1. Blockers for Implementing Stream Processing at Scale

- 2. RocksDB and State Management in Apache Flink

- 3. Apache Fluss: Streaming Lakehouse Architecture

- 4. Accelerating Object Storage Access

- Architectural Decision Matrix

- 6. Conclusion and Future Outlook

1. Blockers for Implementing Stream Processing at Scale

Implementing stream processing in a development or testing environment is fundamentally different from deploying it at production scale. Organizations transitioning from batch processing or proof-of-concept streaming applications often encounter a series of interconnected challenges that can delay or derail production deployments.

1.1 State Management Complexity

State management represents one of the most significant challenges in production stream processing. Stateful stream processing applications must maintain information across event processing cycles. This state can range from simple counters and aggregations to complex windowed computations and join operations.

As applications scale, the state size can grow to terabytes, introducing challenges in:

- Storage: Where to persist the state efficiently

- Access latency: How to retrieve state quickly for processing

- Fault tolerance: How to recover state after failures

- Checkpointing: How to snapshot state without blocking processing

The choice of state backend directly impacts checkpoint duration, recovery time, and overall application throughput. The operational complexity of managing large state includes state migration during schema changes, the impact of state size on job rescaling operations, and careful tuning of checkpoint configurations.

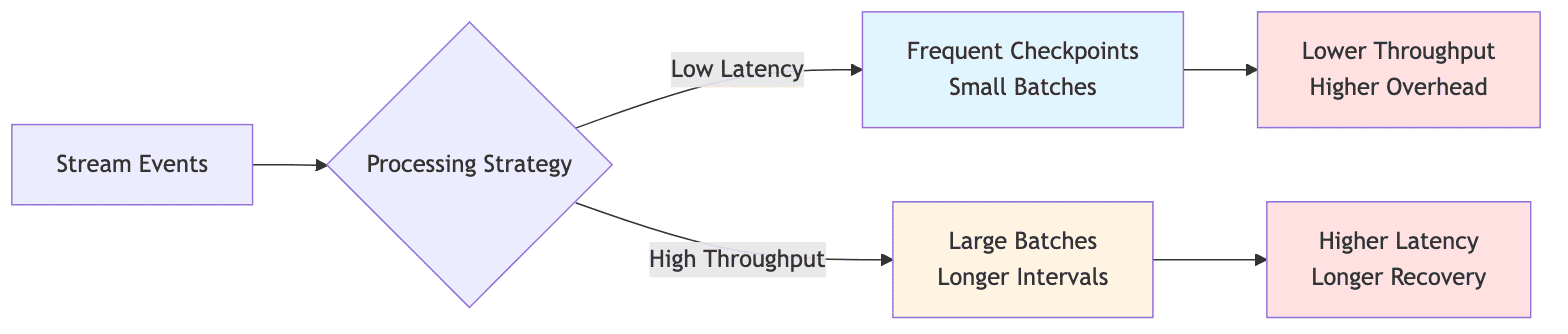

1.2 Latency and Throughput Trade-offs

Stream processing systems must balance latency and throughput requirements, which often conflict. Low-latency processing requires:

- Frequent checkpointing

- Smaller batch sizes

- More frequent state access

But this approach can reduce overall throughput and increase overhead on the state backend.

Conversely, optimizing for throughput by increasing batch sizes and checkpoint intervals introduces:

- Higher latency

- Larger recovery windows

- Greater potential data loss

In production environments, this trade-off becomes particularly acute when serving real-time dashboards or alerting systems that require sub-second data freshness while processing millions of events per second.

1.3 Data Access Patterns and External Lookups

Many stream processing applications require enrichment with reference data or joining with slowly changing dimension tables. This necessitates frequent lookups against external data stores, which can become a significant source of latency.

Object storage systems like Amazon S3, while cost-effective and scalable, introduce access latencies that can be prohibitive for real-time processing. Organizations must implement caching strategies, but caching introduces its own challenges:

- Cache invalidation: Ensuring stale data is removed

- Consistency: Maintaining accuracy across distributed caches

- Memory management: Balancing cache size with available resources

The complexity multiplies when reference data changes frequently, requiring cache updates without disrupting ongoing stream processing.

1.4 Operational Complexity and Expertise Gap

Stream processing systems require specialized operational expertise that is often scarce in the job market. Configuring Flink clusters for optimal performance requires understanding:

- Memory models and allocation

- Network configurations

- State backend tuning

- Garbage collection patterns

Troubleshooting production issues demands knowledge of:

- Checkpointing mechanisms

- Backpressure behavior

- Task scheduling

- Watermark propagation

The expertise gap is particularly pronounced when organizations transition from managed services to self-hosted deployments, where they must assume responsibility for cluster management, monitoring, and incident response. Many teams discover that the total cost of ownership for stream processing infrastructure extends far beyond hardware and licensing costs.

2. RocksDB and State Management in Apache Flink

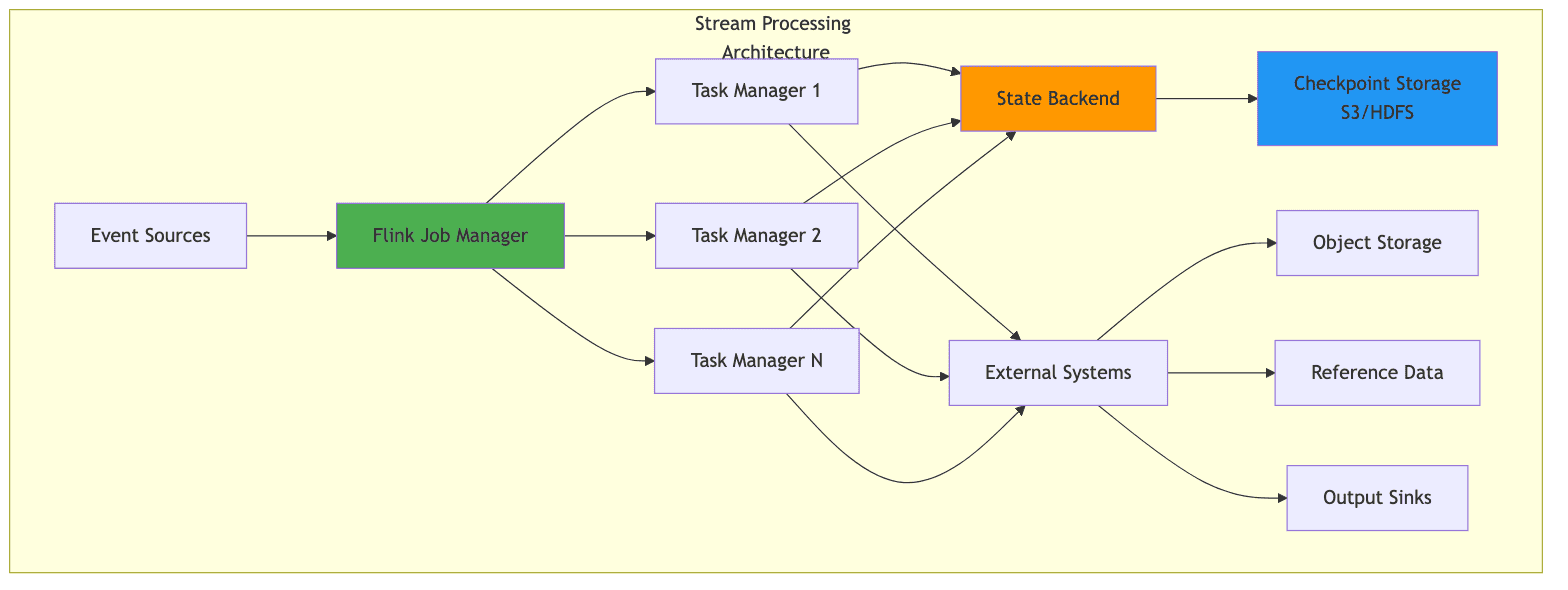

Apache Flink provides two primary production state backends for managing application state:

- HashMapStateBackend: Stores state in the JVM heap (suitable for small state)

- EmbeddedRocksDBStateBackend: Uses an embedded key-value store that persists to local disk, enabling state sizes that far exceed available memory

Note: In Flink versions prior to 1.15, these were called FsStateBackend and RocksDBStateBackend respectively. The naming changed but the underlying concepts remain the same.

Understanding RocksDB's role in Flink's state management is critical for designing and operating production-grade stream processing applications.

2.1 What is RocksDB?

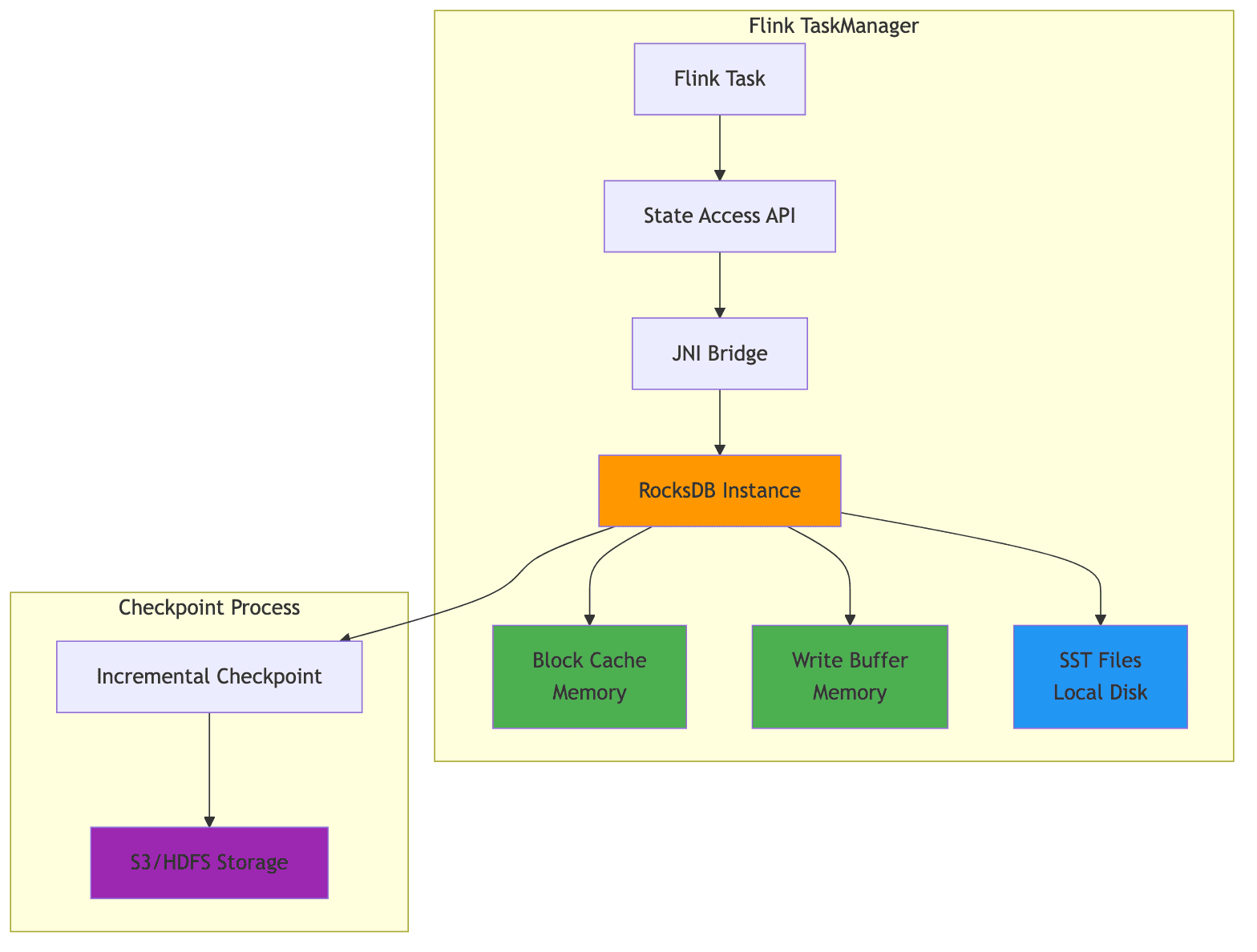

RocksDB is an embeddable persistent key-value store developed at Facebook, based on Google's LevelDB. It is designed for fast storage (SSDs) and provides efficient storage and retrieval of key-value pairs.

Key characteristics:

- Embedded library: Runs within the application process, not a separate cluster

- LSM-tree structure: Optimized for write-heavy workloads

- JNI integration: Flink communicates with RocksDB through Java Native Interface

- Disk-based working state: Stores working state on local disk with memory caching

- Distributed checkpoint storage: Checkpoints are stored in distributed file systems (S3, HDFS, etc.)

Unlike distributed databases that require separate cluster management, RocksDB runs as a library embedded within the application process. In Flink, RocksDB is embedded in TaskManager processes and interacts with the JVM through the Java Native Interface (JNI).

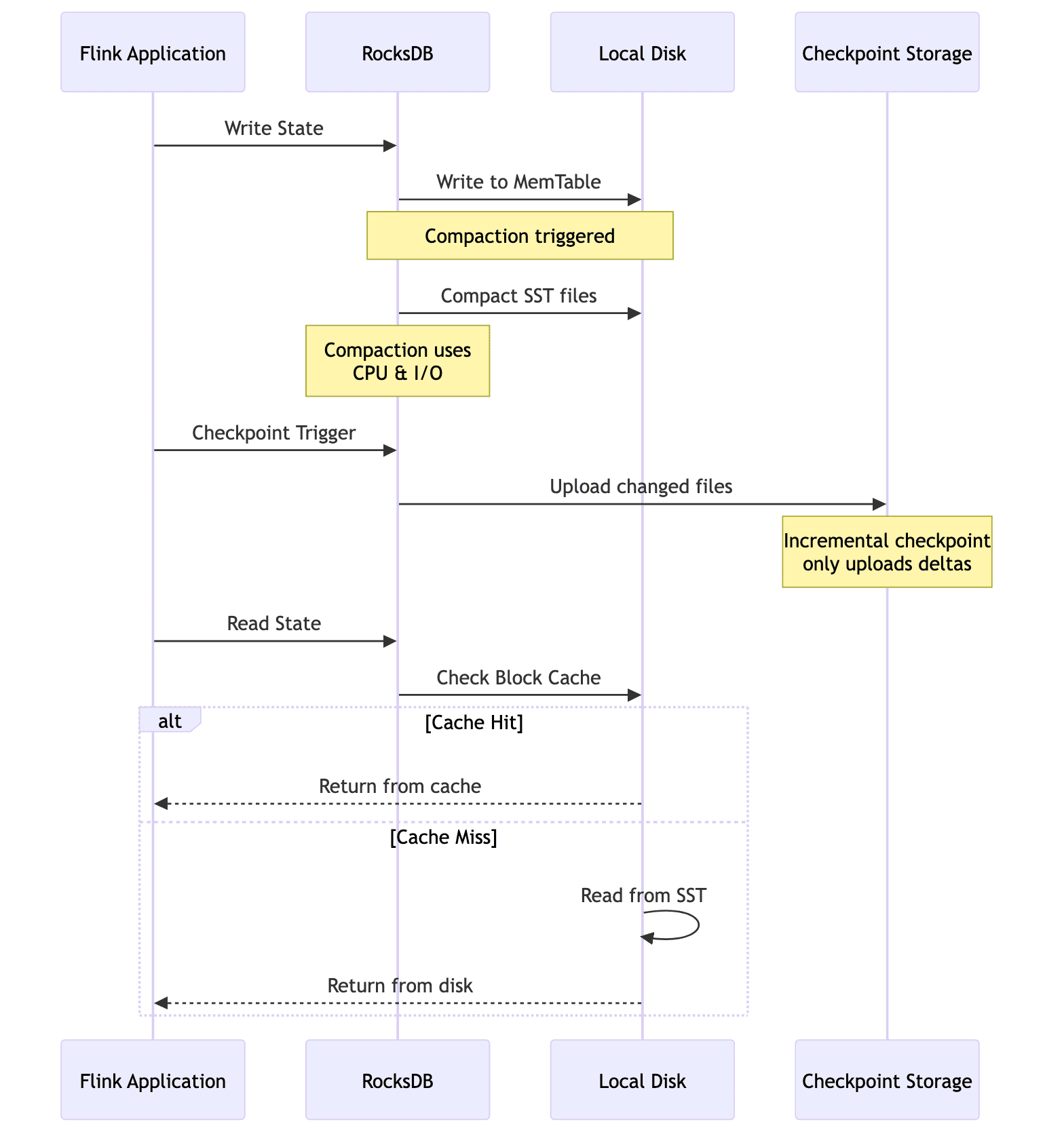

When using EmbeddedRocksDBStateBackend, the working state resides on local disk, but checkpoints (snapshots of state) are stored in distributed storage like S3 or HDFS. Incremental checkpoints only upload the changed SST file deltas, significantly reducing checkpoint overhead for large states.

2.2 When to Use EmbeddedRocksDBStateBackend

The EmbeddedRocksDBStateBackend is the appropriate choice when:

- Large state sizes: Application state exceeds what can reasonably fit in JVM heap memory

- Long window durations: Applications maintain extensive historical context

- Complex keyed state: Applications with large keyed state requirements

- Incremental checkpointing: Need for reduced checkpoint duration

Since RocksDB stores state off-heap and on disk, it provides more predictable latency by avoiding the impact of garbage collection pauses that can affect heap-based state backends. However, this comes at the cost of higher per-access latency due to serialization overhead and disk I/O.

Comparison of State Backends:

| Feature | HashMapStateBackend | EmbeddedRocksDBStateBackend |

|---|---|---|

| State Location | JVM Heap | Off-heap (RocksDB on disk) |

| Checkpoint Storage | Distributed FS | Distributed FS |

| State Size Limit | Limited by heap | Limited by disk |

| Access Latency | Lowest | Higher (serialization + disk I/O) |

| GC Impact | High | Low |

| Incremental Checkpoints | No | Yes |

| Production Ready | Yes (small to medium state) | Yes (large state) |

| Best For | State < few GB | State > tens of GB |

2.3 State Management Problems at Scale

As state sizes grow into the terabyte range, organizations encounter several challenges with RocksDB-based state management:

1. Checkpoint Duration

Even with incremental checkpointing enabled, large checkpoints consume network bandwidth and storage I/O, potentially impacting the performance of other operations. Checkpoint duration directly affects the Recovery Point Objective (RPO) of your streaming application.

2. Recovery Time

Recovery time after failures increases with state size, as the application must restore state from the checkpoint location. This recovery time can violate service level agreements for mission-critical applications. For very large states, recovery can take hours.

3. Rescaling Operations

When the parallelism of a job is changed, state must be redistributed across TaskManagers. This can take hours for very large states and requires careful planning to minimize downtime.

4. Background Operations

Background operations in RocksDB, such as compaction and flushing, can interfere with stream processing performance. When RocksDB compacts files in the background, it consumes CPU and I/O resources that would otherwise be available for event processing, causing unpredictable latency spikes. This is especially visible under write-heavy workloads with high key cardinality, where many SST files are generated and require frequent compaction.

5. Memory Management

Each column family in RocksDB maintains its own block cache and write buffers. Improper configuration can lead to excessive memory usage or suboptimal cache hit rates.

2.4 Configuration Best Practices

Configuring RocksDB for production workloads requires attention to several key parameters:

1. Local Storage Configuration

The local directory for RocksDB files should be on high-performance local storage, ideally SSDs, rather than network-attached storage.

2. Memory Management

Flink's managed memory system (introduced in Flink 1.10) automatically allocates memory for RocksDB. For fine-grained control, you can disable managed memory and configure block cache and write buffer sizes explicitly.

3. Background Threads

The number of background threads should be increased from the default for machines with many CPU cores, as this parallelizes compaction and flushing operations.

4. Bloom Filters

For applications with frequent read operations, enabling bloom filters can significantly reduce disk reads by quickly determining whether a key might exist in a file.

Configuration Example (flink-conf.yaml):

1# Enable RocksDB state backend with incremental checkpointing 2state.backend.type: rocksdb 3state.backend.incremental: true 4state.checkpoints.dir: s3://your-bucket/flink-checkpoints 5 6# RocksDB local directory on high-performance SSD 7state.backend.rocksdb.localdir: /mnt/ssd/rocksdb 8 9# Enable managed memory for RocksDB 10state.backend.rocksdb.memory.managed: true 11 12# Enable predefined options for better performance 13state.backend.rocksdb.predefined-options: SPINNING_DISK_OPTIMIZED_HIGH_MEM 14 15# Write buffer configuration 16state.backend.rocksdb.writebuffer.size: 64mb 17state.backend.rocksdb.writebuffer.count: 4 18 19# Block cache size (if not using managed memory) 20state.backend.rocksdb.block.cache-size: 256mb 21 22# Checkpoint configuration 23execution.checkpointing.interval: 5min 24execution.checkpointing.mode: EXACTLY_ONCE 25execution.checkpointing.timeout: 10min 26

Note: Some configuration keys vary by Flink version. For fine-grained control over RocksDB behavior (such as background thread tuning), use RocksDBOptionsFactory for programmatic configuration.

Programmatic Configuration:

1// Configure RocksDB state backend programmatically 2EmbeddedRocksDBStateBackend backend = new EmbeddedRocksDBStateBackend(true); 3 4// Set local directory 5backend.setDbStoragePath("/mnt/ssd/rocksdb"); 6 7// Configure predefined options 8backend.setPredefinedOptions(PredefinedOptions.SPINNING_DISK_OPTIMIZED_HIGH_MEM); 9 10// Set custom RocksDB options 11backend.setRocksDBOptions(new RocksDBOptionsFactory() { 12 @Override 13 public DBOptions createDBOptions(DBOptions currentOptions, Collection<AutoCloseable> handlesToClose) { 14 return currentOptions 15 .setMaxBackgroundJobs(8) 16 .setMaxOpenFiles(-1) 17 .setStatsDumpPeriodSec(0); 18 } 19 20 @Override 21 public ColumnFamilyOptions createColumnOptions(ColumnFamilyOptions currentOptions, Collection<AutoCloseable> handlesToClose) { 22 return currentOptions 23 .setTableFormatConfig( 24 new BlockBasedTableConfig() 25 .setBlockSize(128 * 1024) 26 .setBlockCacheSize(256 * 1024 * 1024) 27 .setFilterPolicy(new BloomFilter(10, false)) 28 ) 29 .setWriteBufferSize(64 * 1024 * 1024) 30 .setMaxWriteBufferNumber(4); 31 } 32}); 33 34// Note: setStateBackend() is deprecated in Flink 1.15+ 35// Prefer using configuration file or StreamExecutionEnvironment.configure() 36env.setStateBackend(backend); 37

3. Apache Fluss: Streaming Lakehouse Architecture

Apache Fluss (currently incubating) represents a significant evolution in the stream processing landscape by addressing the fundamental tension between real-time streaming and analytical lakehouse architectures.

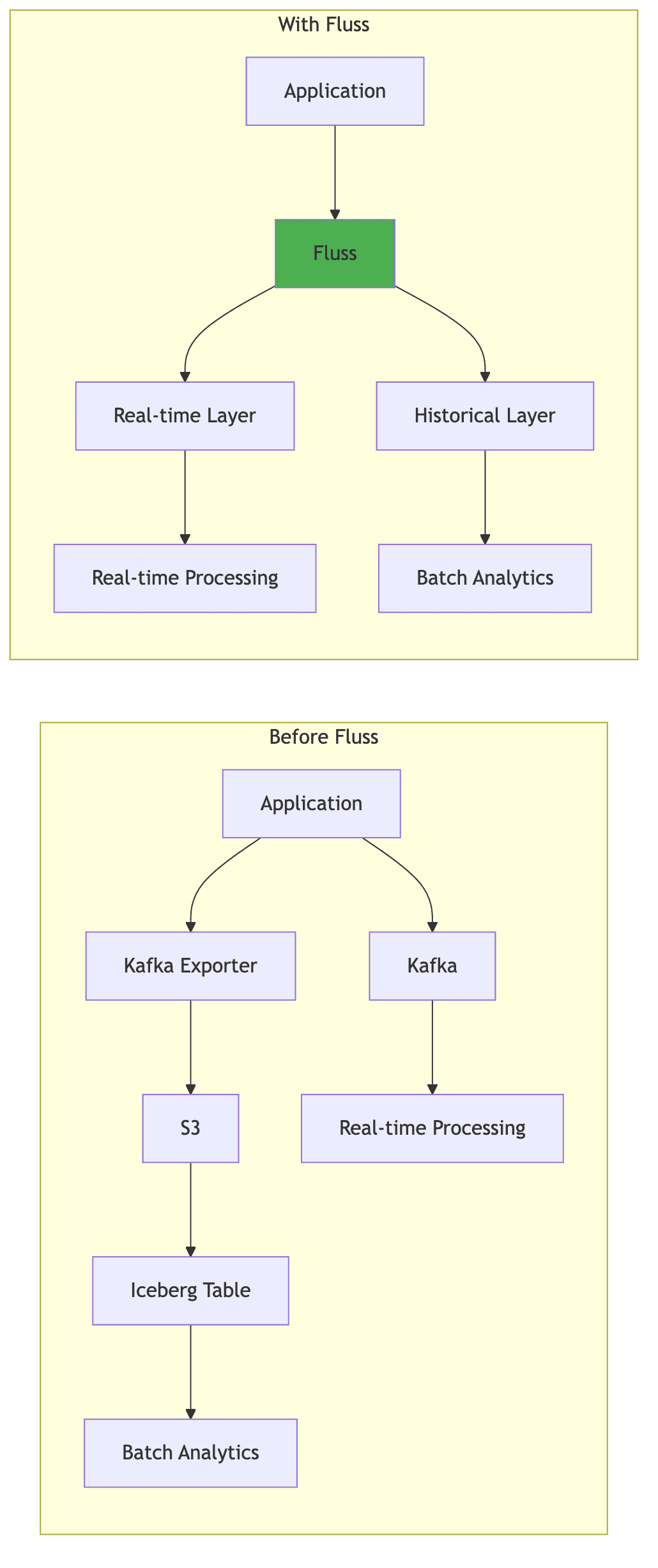

Traditional lakehouse formats like Apache Iceberg, Apache Hudi, and Delta Lake excel at providing ACID transactions, schema evolution, and efficient analytical queries on data lakes. However, they struggle to provide sub-second data freshness due to the inherent trade-off between write frequency and read efficiency. Frequent writes create many small files that are inefficient for queries, while batching writes for efficiency increases latency.

Important Note: Fluss is not a replacement for Kafka in all cases. While Kafka is a distributed log for high-throughput pub-sub messaging, Fluss combines log semantics with lakehouse semantics, making it ideal for scenarios where you need both real-time streaming and immediate analytical access to the same data. For pure streaming use cases without analytical requirements, Kafka remains the simpler choice.

3.1 The Streaming Lakehouse Concept

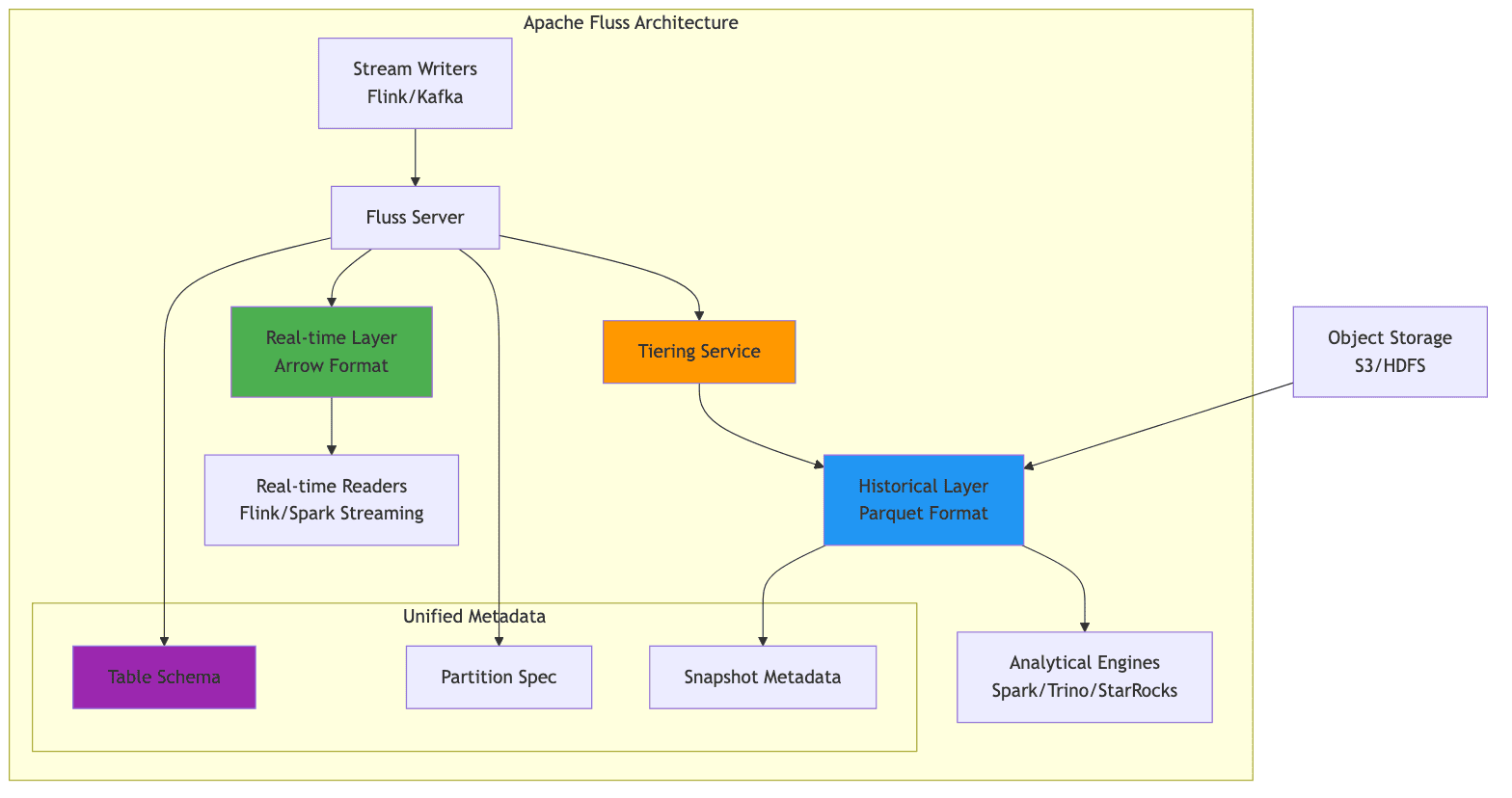

Fluss introduces the concept of a "Streaming Lakehouse" that unifies real-time streaming data with historical lakehouse data. It achieves this by maintaining two complementary data layers:

- Real-time Layer: Stores data in streaming-optimized Arrow format for sub-second access

- Historical Layer: Stores compacted data in Parquet format for efficient analytical queries

A tiering service continuously compacts data from the real-time layer to the historical layer, maintaining consistency between both representations. This architecture allows applications to access truly real-time data through the streaming layer while benefiting from the query efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the lakehouse format for historical analysis.

3.2 Key Features and Benefits

Fluss provides several key features that address common challenges in stream processing architectures:

1. Unified Metadata

Fluss allows users to manage a single table definition that encompasses both real-time and historical data. This eliminates the complexity of maintaining separate streaming and batch tables with synchronized schemas.

2. Union Reads

Queries transparently combine data from both the real-time and historical layers, providing a complete view without requiring users to understand the underlying data organization.

1-- Query automatically combines real-time and historical data 2SELECT customer_id, SUM(amount) as total_spend 3FROM fluss_catalog.ecommerce.orders 4WHERE order_date >= '2026-01-01' 5GROUP BY customer_id; 6

3. Low-Latency Writes

Flink applications can write to Fluss with low latency, similar to writing to Kafka, while simultaneously providing lakehouse access to the same data.

4. Multiple Lakehouse Formats

Fluss currently supports Apache Paimon, Apache Iceberg, and Lance as lakehouse storage formats, providing flexibility in choosing the appropriate format for specific use cases.

5. Automatic Tiering

The tiering service automatically manages the lifecycle of data, moving it from the real-time layer to the historical layer based on configurable policies.

Architecture Comparison:

| Traditional Approach | With Fluss |

|---|---|

| Separate Kafka + Data Lake | Unified streaming storage |

| Dual ingestion pipelines | Single write path |

| Minutes to hours latency | Sub-second latency |

| Schema sync complexity | Unified schema management |

| Separate metadata | Single metadata layer |

3.3 Appropriate Use Cases

Fluss is particularly well-suited for:

1. Real-time Operational Analytics

E-commerce platforms that need real-time inventory dashboards alongside historical sales analysis represent a prime use case. The real-time layer provides up-to-the-second inventory levels, while the historical layer enables trend analysis and forecasting.

2. Financial Services

Financial institutions requiring real-time fraud detection with the ability to perform historical pattern analysis benefit significantly from Fluss's architecture. The real-time layer powers fraud detection models, while the historical layer enables compliance reporting and forensic analysis.

3. Simplified Architecture

Organizations currently maintaining separate Kafka topics for streaming and batch exports to data lakes can simplify their architecture by adopting Fluss as a unified streaming storage layer.

4. IoT and Sensor Data

IoT applications that need to react to sensor data in real-time while maintaining long-term historical data for analysis and machine learning model training.

When Not to Use Fluss:

For applications that only require either pure streaming or pure batch processing, the additional complexity of Fluss may not be justified. Additionally, organizations without the operational expertise to manage a new storage system should carefully evaluate the trade-offs.

4. Accelerating Object Storage Access

Object storage systems such as Amazon S3, Google Cloud Storage, and Azure Blob Storage have become the default choice for storing large volumes of data due to their scalability, durability, and cost-effectiveness. However, their access latency, particularly for random read patterns, can be problematic for stream processing workloads that require low-latency access to reference data or dimension tables.

Caching layers address this challenge by providing a high-performance buffer between compute engines and object storage. There are two architectural approaches to accelerating object storage access:

- File-level acceleration: Transparent caching of files and objects (e.g., Alluxio)

- Data-level acceleration: Materialized key-value or SQL grids that pre-load data into memory (e.g., Apache Ignite)

The choice between these approaches depends on your access patterns, consistency requirements, and operational constraints.

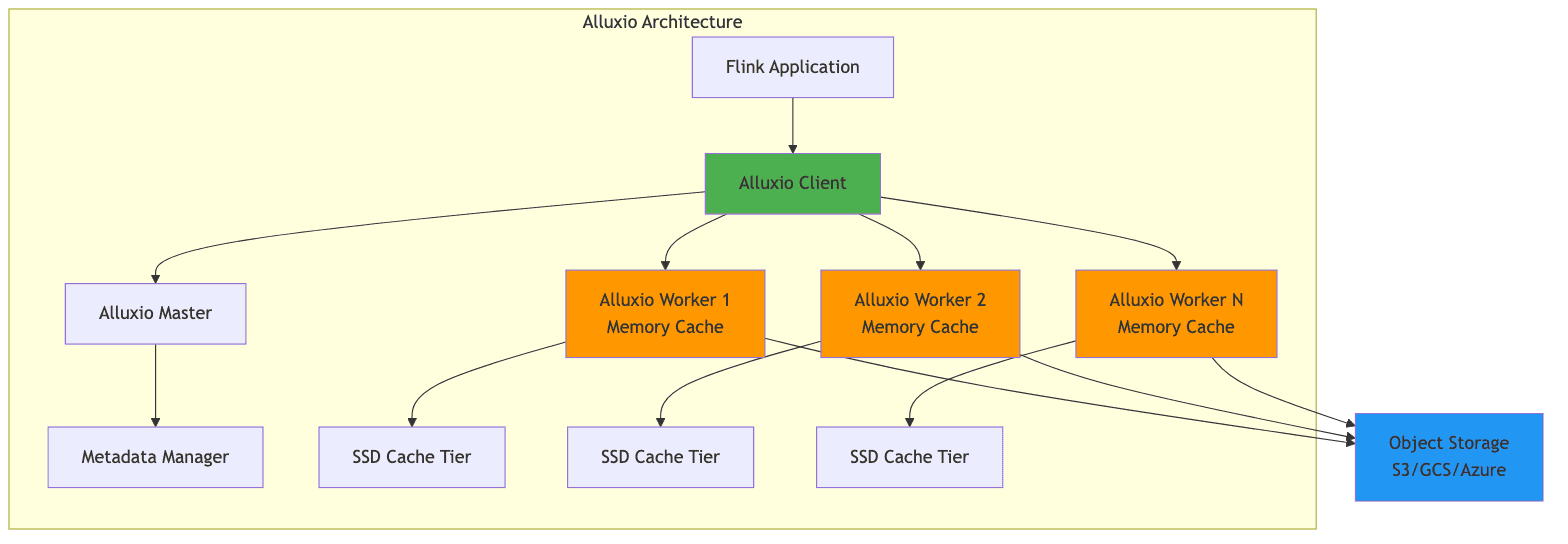

4.1 Alluxio: Distributed Data Orchestration

Alluxio is a distributed caching layer that sits between compute frameworks and storage systems, providing data orchestration and acceleration. It presents a unified namespace that can mount multiple underlying storage systems, transparently caching frequently accessed data in memory or on local SSDs.

Key Benefits for Stream Processing:

- Reduced Latency: Cache dimension tables and reference data that are frequently accessed during join operations

- Higher Throughput: Serve data from local cache instead of making repeated calls to object storage

- Cost Savings: Reduced API calls to object storage can translate to significant cost savings at scale

- Write Caching: Alluxio AI 3.8 introduced write caching, addressing the bottleneck of writing results back to object storage

Use Cases in Stream Processing:

1. Dimension Table Joins with Flink SQL

The most practical way to leverage Alluxio in stream processing is through Flink's SQL API, where entire dimension tables stored as Parquet files are accessed through the Alluxio cache.

1-- Configure Alluxio as the file system (done at cluster level) 2-- Flink jobs access files via alluxio:// protocol 3 4-- Create a dimension table backed by Parquet files in Alluxio 5CREATE TABLE product_dimensions ( 6 product_id STRING, 7 product_name STRING, 8 category STRING, 9 price DECIMAL(10, 2) 10) WITH ( 11 'connector' = 'filesystem', 12 'path' = 'alluxio://master:19998/dimensions/products', 13 'format' = 'parquet' 14); 15 16-- Kafka source table 17CREATE TABLE order_stream ( 18 order_id STRING, 19 product_id STRING, 20 quantity INT, 21 order_time TIMESTAMP(3) 22) WITH ( 23 'connector' = 'kafka', 24 'topic' = 'orders', 25 'properties.bootstrap.servers' = 'kafka:9092', 26 'format' = 'json' 27); 28 29-- Join streaming orders with cached dimension table 30-- Alluxio transparently caches the Parquet files for fast repeated access 31SELECT 32 o.order_id, 33 o.product_id, 34 p.product_name, 35 p.category, 36 o.quantity, 37 o.quantity * p.price as order_value 38FROM order_stream o 39LEFT JOIN product_dimensions FOR SYSTEM_TIME AS OF o.order_time AS p 40ON o.product_id = p.product_id; 41

2. Broadcast State with Alluxio-Cached Data

For DataStream API, load dimension data from Alluxio-cached files into broadcast state:

1// Alluxio is configured at cluster level via flink-conf.yaml 2// alluxio.master.hostname=master 3// alluxio.master.port=19998 4 5// Read dimension data from Alluxio path 6// The files are transparently cached by Alluxio 7FileSource<Product> dimensionSource = FileSource 8 .forRecordStreamFormat(new ParquetReaderFactory<>(), 9 new Path("alluxio://master:19998/dimensions/products.parquet")) 10 .build(); 11 12// Load into broadcast state for enrichment 13MapStateDescriptor<String, Product> dimensionStateDesc = 14 new MapStateDescriptor<>("dimensions", String.class, Product.class); 15 16BroadcastStream<Product> dimensionBroadcast = env 17 .fromSource(dimensionSource, WatermarkStrategy.noWatermarks(), "Dimensions") 18 .broadcast(dimensionStateDesc); 19 20// Main event stream 21DataStream<Order> orders = env.addSource(new KafkaSource<>(...)); 22 23// Enrich orders with broadcast dimension data 24DataStream<EnrichedOrder> enriched = orders 25 .connect(dimensionBroadcast) 26 .process(new BroadcastProcessFunction<Order, Product, EnrichedOrder>() { 27 @Override 28 public void processElement(Order order, 29 ReadOnlyContext ctx, 30 Collector<EnrichedOrder> out) { 31 ReadOnlyBroadcastState<String, Product> state = 32 ctx.getBroadcastState(dimensionStateDesc); 33 Product product = state.get(order.getProductId()); 34 out.collect(new EnrichedOrder(order, product)); 35 } 36 37 @Override 38 public void processBroadcastElement(Product product, 39 Context ctx, 40 Collector<EnrichedOrder> out) { 41 ctx.getBroadcastState(dimensionStateDesc) 42 .put(product.getId(), product); 43 } 44 }); 45

Key Points:

- Alluxio is configured at the cluster level, not within individual jobs

- It provides transparent caching—Flink reads from

alluxio://paths like any file system - Best for scenarios where dimension data is read repeatedly by multiple jobs

- Reduces S3 API calls and improves read throughput for frequently accessed files

Configuration:

1# Alluxio configuration for stream processing 2alluxio.user.file.cache.enabled=true 3alluxio.user.file.readtype.default=CACHE 4alluxio.user.file.writetype.default=CACHE_THROUGH 5 6# Memory allocation 7alluxio.worker.memory.size=32GB 8alluxio.worker.tieredstore.levels=2 9alluxio.worker.tieredstore.level0.alias=MEM 10alluxio.worker.tieredstore.level0.dirs.path=/mnt/ramdisk 11alluxio.worker.tieredstore.level1.alias=SSD 12alluxio.worker.tieredstore.level1.dirs.path=/mnt/ssd 13

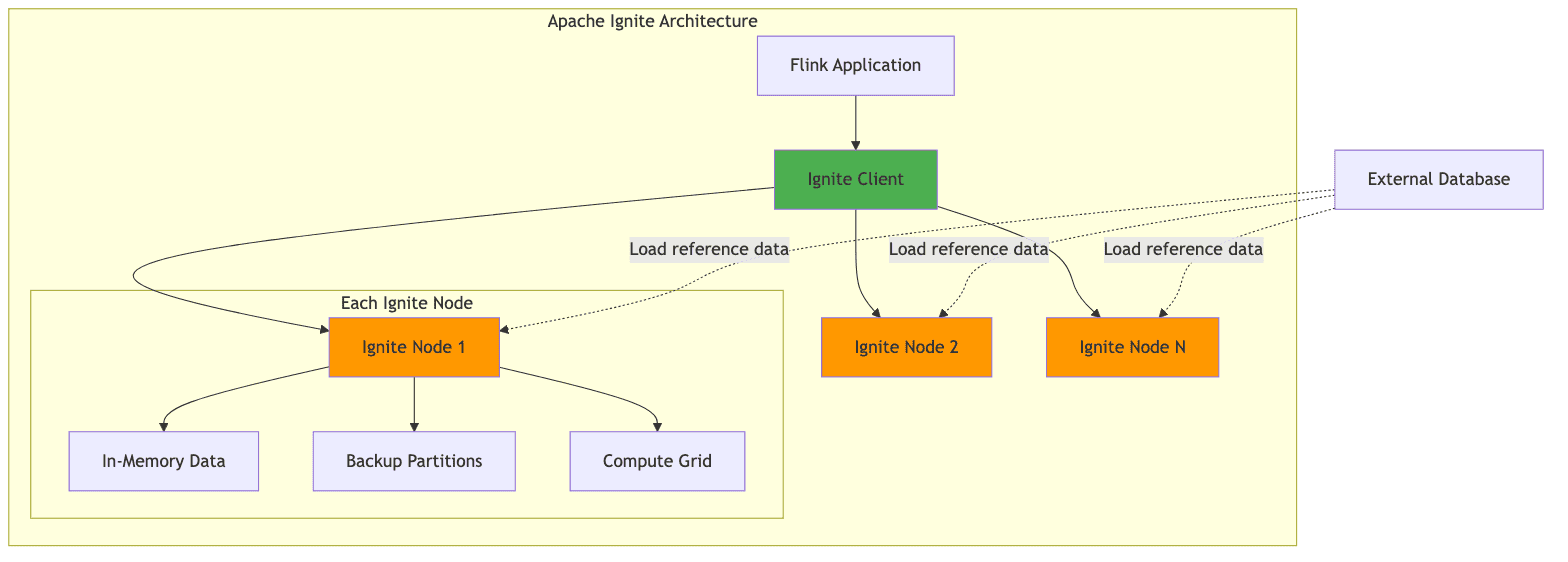

4.2 Apache Ignite: In-Memory Data Grid

Apache Ignite provides a different approach to data acceleration through its in-memory data grid capabilities. Unlike Alluxio, which focuses on file-based caching, Ignite provides a distributed key-value store that can be used directly for caching reference data.

Key Features:

- Sub-millisecond Access: Cached data with sub-millisecond access times

- SQL Capabilities: Query cached data using standard SQL syntax

- Distributed Transactions: ACID transactions across the data grid

- Compute Co-location: Run computations where data is cached

Use Cases in Stream Processing:

1. Real-time Lookups

1// Flink enrichment with Ignite cache 2public class IgniteEnrichmentFunction extends RichMapFunction<Event, EnrichedEvent> { 3 private static transient Ignite ignite; // Static to share across instances 4 private transient IgniteCache<String, Customer> customerCache; 5 6 @Override 7 public void open(Configuration parameters) { 8 // Use singleton pattern to avoid multiple Ignite client instances 9 if (ignite == null) { 10 synchronized (IgniteEnrichmentFunction.class) { 11 if (ignite == null) { 12 IgniteConfiguration cfg = new IgniteConfiguration(); 13 cfg.setClientMode(true); 14 cfg.setIgniteInstanceName("flink-ignite-client"); 15 ignite = Ignition.start(cfg); 16 } 17 } 18 } 19 customerCache = ignite.cache("customers"); 20 } 21 22 @Override 23 public EnrichedEvent map(Event event) { 24 // Sub-millisecond lookup 25 Customer customer = customerCache.get(event.getCustomerId()); 26 return new EnrichedEvent(event, customer); 27 } 28 29 @Override 30 public void close() { 31 // Don't close static Ignite instance 32 // It will be shared across all operator instances 33 } 34} 35

2. Distributed Counters with Proper Atomicity

1// Use Ignite's distributed atomic types for shared aggregation state 2public class SharedStateAggregation extends RichFlatMapFunction<Event, Aggregation> { 3 private static transient Ignite ignite; 4 5 @Override 6 public void open(Configuration parameters) { 7 if (ignite == null) { 8 synchronized (SharedStateAggregation.class) { 9 if (ignite == null) { 10 IgniteConfiguration cfg = new IgniteConfiguration(); 11 cfg.setClientMode(true); 12 ignite = Ignition.start(cfg); 13 } 14 } 15 } 16 } 17 18 @Override 19 public void flatMap(Event event, Collector<Aggregation> out) { 20 String key = event.getAggregationKey(); 21 22 // Use IgniteAtomicLong for distributed atomic operations 23 // This ensures thread-safe distributed increments 24 IgniteAtomicLong counter = ignite.atomicLong( 25 key, // counter name 26 0, // initial value 27 true // create if not exists 28 ); 29 30 long newValue = counter.incrementAndGet(); 31 out.collect(new Aggregation(key, newValue)); 32 } 33} 34

3. Cache Loading from CDC Stream

1// Keep Ignite cache in sync with source database using CDC 2DataStream<ChangeEvent> cdcStream = env.addSource(new DebeziumSource<>(...)); 3 4cdcStream.addSink(new RichSinkFunction<ChangeEvent>() { 5 private static transient Ignite ignite; 6 private transient IgniteCache<String, Customer> cache; 7 8 @Override 9 public void open(Configuration parameters) { 10 if (ignite == null) { 11 synchronized (this.getClass()) { 12 if (ignite == null) { 13 ignite = Ignition.start(new IgniteConfiguration().setClientMode(true)); 14 } 15 } 16 } 17 cache = ignite.cache("customers"); 18 } 19 20 @Override 21 public void invoke(ChangeEvent event, Context context) { 22 switch (event.getOperation()) { 23 case INSERT: 24 case UPDATE: 25 cache.put(event.getKey(), event.getValue()); 26 break; 27 case DELETE: 28 cache.remove(event.getKey()); 29 break; 30 } 31 } 32}); 33

Key Points:

- Use static singleton pattern for Ignite client to avoid creating multiple instances per operator

- Use

IgniteAtomicLongfor distributed atomic operations, not Java'sAtomicLong - Ignite provides strong consistency guarantees for cache operations

- Best for key-value lookups with frequent updates (e.g., dimension tables, aggregation state)

Comparison: Alluxio vs Apache Ignite

| Feature | Alluxio | Apache Ignite |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | File-based caching | Key-value caching |

| Data Model | Files/Objects | Key-value, SQL |

| Access Pattern | File I/O | Get/Put, SQL queries |

| Best For | Parquet/Avro files | Dimension tables |

| Latency | Low (cached files) | Very low (in-memory) |

| Query Support | Via mounted engines | Native SQL |

| Consistency Model | Transparent caching | Strong consistency |

| Write Support | Cache-through | Direct writes |

4.3 Implementation Considerations

Implementing caching layers requires careful consideration of several factors:

1. Consistency and Invalidation

Stream processing applications often require access to the latest version of reference data. Cache invalidation strategies must ensure that stale data is either evicted or updated when the source data changes.

Alluxio TTL-based Invalidation:

1# Set TTL for cached dimension tables 2alluxio.user.file.metadata.sync.interval=5min 3alluxio.user.file.passive.cache.enabled=true 4

Ignite Change Data Capture:

1// Update Ignite cache from CDC stream 2DataStream<ChangeEvent> cdcStream = env.addSource(new DebeziumSource<>(...)); 3 4cdcStream.addSink(new RichSinkFunction<ChangeEvent>() { 5 private transient IgniteCache<String, Customer> cache; 6 7 @Override 8 public void open(Configuration parameters) { 9 cache = Ignition.start(config).cache("customers"); 10 } 11 12 @Override 13 public void invoke(ChangeEvent event, Context context) { 14 switch (event.getOperation()) { 15 case INSERT: 16 case UPDATE: 17 cache.put(event.getKey(), event.getValue()); 18 break; 19 case DELETE: 20 cache.remove(event.getKey()); 21 break; 22 } 23 } 24}); 25

2. Resource Management

Caching layers require dedicated memory and potentially SSD storage, which must be provisioned appropriately to avoid impacting the resources available for stream processing itself.

1# Kubernetes deployment with resource allocation 2apiVersion: v1 3kind: Pod 4metadata: 5 name: flink-taskmanager 6spec: 7 containers: 8 - name: taskmanager 9 resources: 10 requests: 11 memory: "8Gi" 12 cpu: "4" 13 limits: 14 memory: "16Gi" 15 cpu: "8" 16 - name: alluxio-worker 17 resources: 18 requests: 19 memory: "32Gi" 20 cpu: "2" 21 limits: 22 memory: "64Gi" 23 cpu: "4" 24

3. Monitoring

Monitoring cache hit rates, eviction rates, and access latency is essential for tuning the caching configuration and justifying the infrastructure investment.

Key Metrics to Monitor:

- Cache hit rate

- Cache miss rate

- Average access latency

- Eviction rate

- Memory utilization

- Network throughput

- Object storage API call reduction

1// Expose Alluxio metrics to Prometheus 2MetricRegistry registry = AlluxioWorkerMonitor.getMetricRegistry(); 3registry.gauge("cache.hit.rate", () -> 4 (double) cacheHits / (cacheHits + cacheMisses) 5); 6

4. Production Cost Considerations

Understanding the cost implications of different caching strategies is critical for production deployments:

S3 API Call Costs:

- Without caching: If a dimension table is read 1000 times/sec, that's 86.4M GET requests/day

- At 34.56/day or ~$1,000/month just for reads

- With Alluxio caching: Reduced to initial load + occasional refreshes = ~$1-2/month

Checkpoint Storage Growth:

- RocksDB incremental checkpoints grow metadata over time

- Without cleanup, metadata can reach hundreds of GB

- Recommendation: Enable checkpoint retention and expired snapshot cleanup

- Configure

state.checkpoints.num-retained: 3to limit storage costs

Cache Infrastructure Costs:

- Alluxio worker with 64GB RAM + 1TB NVMe SSD: ~$200-300/month per node

- Apache Ignite with 128GB RAM: ~$400-500/month per node

- ROI calculation: Cache cost vs. S3 API costs + latency improvement value

5. Failure Mode Analysis

Understanding failure modes helps design more resilient systems:

| Failure Scenario | Impact | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| RocksDB local SSD failure | Task failure, restore from checkpoint | Use RAID or redundant disks; fast SSD replacement |

| Cold cache (Alluxio restart) | Temporary performance degradation | Gradual warm-up; prioritize critical datasets |

| Ignite node failure | Backup partitions serve requests | Configure backup count ≥ 2 |

| Checkpoint storage unavailable | Cannot create checkpoints; risk of data loss | Use highly available storage (S3, HDFS HA) |

| Large state backfill | Hours of replay, high resource usage | Pre-warm state; use savepoints for planned restarts |

Cold Cache Scenario:

When Alluxio restarts, all cached data is lost. The first access will be slow (S3 latency), but subsequent accesses will benefit from the cache. To minimize impact:

- Implement gradual warm-up by pre-loading critical datasets

- Use Alluxio's pinning feature for high-priority data

- Monitor cache miss rate and alert on sustained high values

Architectural Decision Matrix

Choosing the right technology for your stream processing challenges requires understanding the trade-offs. Here's a decision matrix to guide your architectural choices:

| Problem | Solution | Primary Benefit | Key Trade-off | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large keyed state (>100GB) | EmbeddedRocksDBStateBackend | Unlimited state size | Higher access latency (serialization) | State exceeds heap memory |

| Small state (<10GB) | HashMapStateBackend | Lowest latency | Limited by heap size | Fast state access critical |

| Streaming + batch analytics | Apache Fluss | Unified real-time + historical data | New infrastructure to manage | Need sub-second fresh analytics |

| S3 lookup latency | Alluxio | Transparent file caching | Additional memory tier required | Repeated file access patterns |

| Dimension table lookups | Apache Ignite | Sub-millisecond KV access | Consistency management overhead | High-frequency KV lookups |

| Checkpoint duration | Incremental checkpoints | Only upload deltas | Metadata accumulation | State >100GB |

| Recovery time | Smaller checkpoints + local state | Faster restore | Less fault tolerance | Low RTO requirements |

| Schema evolution | Fluss unified metadata | Single schema for stream + batch | Coupled architecture | Frequent schema changes |

Decision Tree for State Backend:

1State Size? 2├─ <5GB → HashMapStateBackend 3├─ 5-50GB → Either (benchmark both) 4└─ >50GB → EmbeddedRocksDBStateBackend 5 └─ Enable incremental checkpointing 6

Decision Tree for Caching:

1Access Pattern? 2├─ File-based (Parquet, Avro) 3│ └─ Alluxio 4│ └─ Configure tiered storage (Memory → SSD) 5└─ Key-value lookups 6 ├─ Read-heavy → Ignite (replicated mode) 7 └─ Write-heavy → Ignite (partitioned mode) or external DB 8

Decision Tree for Lakehouse Integration:

1Need sub-second fresh analytics? 2├─ Yes → Consider Fluss 3│ └─ Are you maintaining separate Kafka + Data Lake? 4│ ├─ Yes → Strong candidate for Fluss 5│ └─ No → Evaluate operational overhead 6└─ No → Standard Kafka + batch ingestion to lakehouse 7 └─ Latency tolerance >5 minutes 8

6. Conclusion and Future Outlook

Accelerating stream processing in production environments requires a holistic approach that addresses state management, data access patterns, and the integration between streaming and analytical systems.

Key Takeaways:

-

State Management: RocksDB remains the state backend of choice for large-state applications in Flink, but organizations must invest in proper configuration and operational expertise to realize its benefits.

-

Streaming Lakehouse: The emergence of Apache Fluss offers a promising solution to the streaming-lakehouse integration challenge, potentially simplifying architectures that currently require separate systems for real-time and batch processing.

-

Caching Strategies: Caching layers like Alluxio and Apache Ignite provide practical solutions for accelerating data access from object storage, with the choice between them depending on specific access patterns and consistency requirements.

-

Operational Excellence: Success in production stream processing requires more than just technical solutions—it demands operational expertise, comprehensive monitoring, and a deep understanding of the trade-offs involved.

Future Trends:

Several trends are likely to shape the evolution of stream processing acceleration:

1. State Disaggregation

Flink 2.0's proposed architecture promises to separate compute from state storage, potentially reducing recovery times and enabling more flexible scaling. This will allow independent scaling of compute and state resources.

2. Unified Streaming Storage

The continued development of Apache Fluss and similar streaming storage systems will likely blur the distinction between streaming and batch processing further, leading to simpler architectures.

3. AI/ML Integration

The integration of AI and machine learning workloads with stream processing pipelines will drive demand for even lower latency and more sophisticated state management capabilities. Real-time feature stores and online model inference will become first-class citizens in stream processing frameworks.

4. Cloud-Native Evolution

Stream processing systems will continue to evolve towards cloud-native architectures, with better Kubernetes integration, serverless deployment options, and automatic scaling based on workload.

5. Hardware Acceleration

As specialized hardware for data processing (GPUs, FPGAs, smart NICs) becomes more accessible, stream processing frameworks will integrate with these accelerators to achieve even lower latencies.

Organizations investing in stream processing infrastructure should monitor these developments and plan for architectural flexibility as the technology landscape continues to evolve. The key is not to chase every new technology, but to understand the fundamental challenges your organization faces and select solutions that address those specific needs.

Enjoyed this post? Subscribe for more!

We respect your privacy. Unsubscribe at any time.